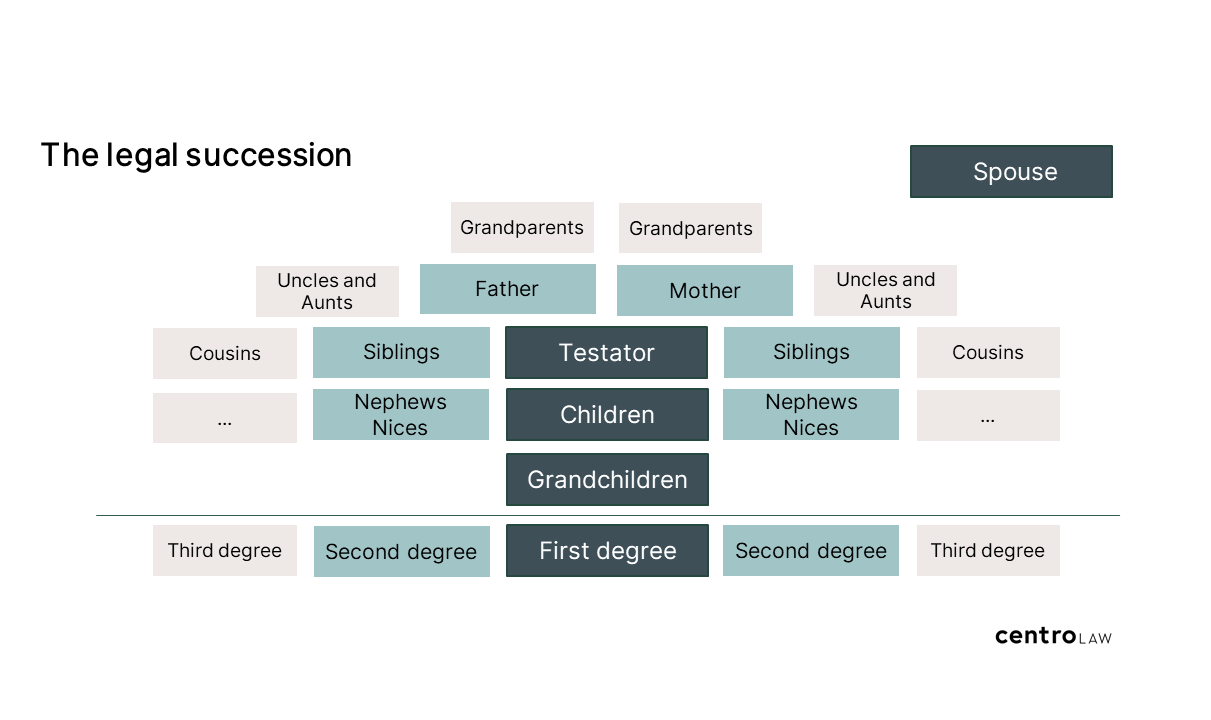

The legal succession

The legal succession rules apply if a testator has not made an arrangement through a disposition of wealth upon death or has only made a partial disposition.

In such an event, the relatives, the surviving spouse or registered partner, and, subsidiarily, the state are deemed to be the legal heirs.

Depending on the relationship with relatives, their resulting portion of the estate is the so-called statutory share.

Blood relatives

The legal system establishes a hierarchy among the relatives into three degrees:

- All descendants of the deceased belong to the first degree. It includes, in addition to the testator's children, their children, and further descendants. This degree contains legitimate, illegitimate, and adopted children.

- Together with their descendants, the testator's parents form the second degree. Thus, the testator's father, mother, brothers, sisters, nephews, nieces, and descendants.

- The testator's grandparents and descendants belong to the third degree. These are uncles and aunts and their descendants.

Only the first three degrees are relevant for legal succession.

How do blood relatives inherit?

In principle, a subsequent degree of relationship only comes into play if no person from the preceding degree is a legal heir.

The first-degree blood relative

If heirs are in the first degree, they exclude the subsequent degrees.

If a testator has children, the other degrees are no longer considered for legal succession.

Within a degree, only the oldest generation inherits primarily, whereby all heirs of this generation are treated equally (principle of equality).

If a testator has children and grandchildren, only the children within this degree are considered in equal shares.

If a person of the oldest generation cannot become an heir within a degree, her descendants take her place (principle of entry).

This may be the case due to predecease, disclaimer of the inheritance, disinheritance, or unworthiness to inherit.

If there are no descendants, the other children inherit the same level (accrual principle).

Each degree is divided into stirpes formed by the oldest generation and their descendants.

The law follows the logic of the principles of equality, entry, and accrual. Only if there is no person in the first degree, the second degree is entitled to inherit.

The second-degree blood relative

The second degree includes the parents of the testator and their descendants. If both parents are alive, each of the parents inherits an equal share.

If the parents are not alive anymore, their descendants will inherit. If one parent is predeceased, the inheritance accrues to the other parent.

If no descendants of the second degree are entitled to inherit either, the inheritance accrues to the third degree.

The third-degree blood relative

The third degree is the last relevant for legal succession. If there are no heirs of the third degree, the inheritance will go to the state.

The third degree includes the grandparents and their descendants.

Again, if all grandparents are alive, they inherit in equal shares. If one of the grandparents is predeceased, her descendants inherit that portion.

If a grandparent is predeceased without descendants, that share will not go to all grandparents equally, but only to the line married to her.

If there are no grandparents or descendants on one line, the entire inheritance goes to the other.

The surviving spouse

In addition to the legal heirs according to degrees, the spouse or registered partner are also entitled to inheritance.

The marriage is dissolved upon the testator's death, and the matrimonial property settlement is carried out before inheritance issues are resolved.

Depending on the applicable property law, this determines which assets are included in the testator's estate.

Next to the first degree, spouses inherit a quota of 1/2.

If there is a second degree, the spouse or registered partner inherits 3/4 of the estate.

In the event of only a third degree, the surviving spouse or registered partner will inherit the entire estate.

If a testator leaves behind a spouse and a child, the spouse inherits 1/2 next to the first degree. As such, the child will also inherit 1/2 of the estate.

If there are no descendants but the testator's parents, the spouse inherits 3/4 of the estate and the parents 1/4.